Published 26th of March 2021

Calls for the abolition of cars with internal combustion engines (ICE) are piling up. Eight EU member states want to ban them in Europe from 2030 onwards. Also in the US, proposals to go fully electric in terms of car registration by 2030 and to ban all ICE cars by 2040 are circulating. The German transport minister, however, would like to set an expiry date not before 2035 and demands not to tighten emission regulations as planned from 2025 onwards. Norway, on the contrary, wants to get rid of ICE cars as early as 2025.

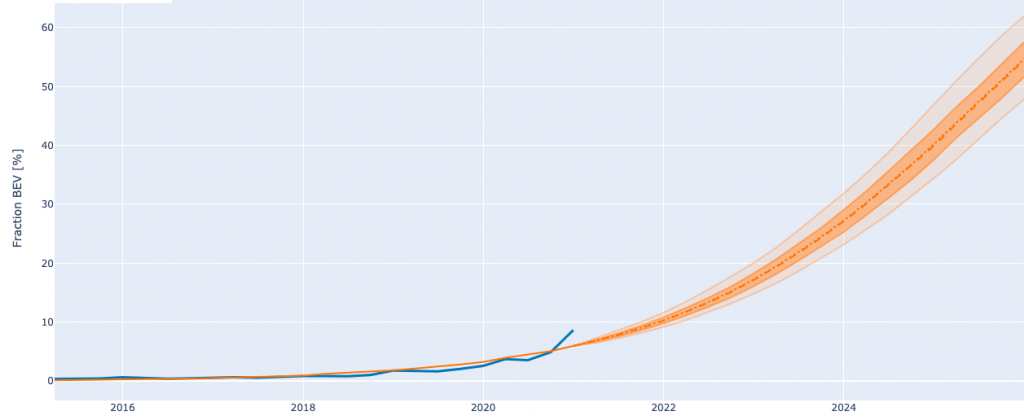

In the fourth quarter of 2020 slightly less than 10% of new registrations in Europe were pure battery electric vehicles (BEVs). Plug-in hybrids – which are also often included in the statistics for electric cars – account for roughly the same number of registrations. As these would be affected by a ban of combustion engines and rarely achieve the consumption and emission figures that are on paper, they are not included in our forecast. Actually, it is difficult to see that plug-in hybrids contribute to achieving emission and climate targets in a significant way.

In fact, estimates of the evolution of BEV’s market share vary widely. Optimists expect sales of electric cars to increase consistently by more than 80% per year. In purely arithmetical terms, European car registration statistics would then be populated by purely electric cars as early as 2024. Vaclav Smil, who recently published a book on growth processes that is well worth reading, believes that forecasts predicting a 50% share of electric cars in new registrations by 2025 are complete fantasy.

According to our econometric forecasts, the share of electric cars in new registrations in the EU will be around 55% at the end of 2025, i.e. growing by about 45% per year. A prerequisite is that the current incentives for electric cars remains in place (or are replaced by a significant carbon tax) and that infrastructure development keeps pace with the exponential growth in registrations. In addition, the electrification of heavy traffic must be taken into account, and – above all – electro-mobility makes most sense if all the electricity comes from renewable energy sources.

Figure 1: Share of all-electric cars in new registrations in the EU

Source: Forecast by cbased based on ACEA data

Note: Actual BEV registrations in % of all registrations in blue, forecast with confidence interval in orange

A virtuous cycle on the demand side

The massive increase in EV registration in the final quarter of 2020 may be influenced by car producers striving to increase the number of EVs sold to meet EU fleet emissions regulations and to avoid penalties. This may have motivated some companies to register cars even if they were not yet sold. It remains to be seen if the fourth quarter was a “game changer” for electro-mobility in Europe and rightly lifted the forecast or was just a “straw fire” fueled by regulations. Forecasts including the fourth quarter signal that car registrations will be fully electric well before 2030 while those not including the fourth quarter will just meet this target in 2030. We will update the forecast once more data is available.

Nonetheless, Europe has overtaken China in terms of registration numbers and is currently by far the most dynamic market. The variety of electric cars on offer has been broadening and prices will continue to fall. BEVs will be cheaper than ICE cars in terms of acquisition price and maintenance costs – the latter is already the case. Thus the outlook for e-mobility is definitely positive and the only feasible way to bring down environmental and climate damage caused by cars. While regulations should not exclude other technologies like synthetic fuels, those are still in their infancy and far from having any impact on emission statistics in the foreseeable future.

There are still a number of challenges in regulating charging infrastructure that have not been adequately addressed to date. Many of the current charging infrastructure operators charge on a per minute basis rather than the kilowatts loaded, offer subscription models with hefty mark-ups for roaming and rip-off prices for customers without subscription. These problems may be acceptable to early adopters of electric cars but are not suitable for the mass market. Also offering sufficient charging options for high e-mobility penetration rates in urban areas is a challenge.

While it seems obvious that the future is electric, the number of new cars demanded might still be difficult to forecast in the long run. Investments in local and long-distance public transport, car sharing solutions and robotaxis (autonomously driving cabs), that reduce the costs of individual mobility substantially, may significantly decrease the urge to own a car. Reinforcing these trends results in better resource-efficiency and less environmental damage and is beneficial both for individuals and society at large but would result in significantly lower numbers of cars sold.

Supply side constraints?

However, the elimination of cars with internal combustion engines from 2030 onwards may not be compatible with the industry’s plans. For example, BMW and VW plan that only 50% of the cars produced in 2030 will be fully electric. At VW, this figure is consistent with the expansion plan for battery production: the envisioned five battery gigafactories will suffice to electrify about half of the cars VW plans to produce. Batteries are likely to be the real bottleneck on the supply side. At Tesla, it is already the case that production of some models had to be postponed because not enough batteries can be produced.

Japanese manufacturers – Nissan being a noteworthy exception – have also been very hesitant about the switch to electro-mobility and have only recently started to take the issue seriously. In contrast, a number of startups in China, the U.S., and few in Europe, are fully committed to electro mobility. Firmly setting an end date for fossil cars may entice foreign electric car manufacturers to set up production plants in Europe as the future of electric cars would be better predictable. Being predictable is the best way to benefit from the ongoing electrification of transportation and to counteract bottlenecks on the supply side.

While an undersupply of electric cars by 2030 seems unlikely, structural change at European automakers might be too slow to fully benefit from this development. Assuming that the US and China will set phasing out dates for fossil cars, it is questionable whether there will be a sufficiently large market to absorb the fossil cars VW and BMW still intend to produce in 2030. Also, why would any countries continue to opt for fossil cars?

Politics trumps economics

“Politics trumps economics” is usually assumed when priorities have to be sorted out. Climate issues, regrettably, seem to be outside the scope of this “rule”. Agreeing on a date to phase out fossil cars at the European level may be difficult. Not only crossfire from lobbyists for internal combustion engines has to be expected but the different BEV diffusion rates across EU member states may be a stumbling block. According to our estimates, electric cars in the EU10 – the “new” member states – will account for only about 27% in new registrations in 2025. The problem is not the availability of affordable electric cars – there will be plenty of those in the near future – but the development of infrastructure, which is still lagging behind in these countries. Speeding up infrastructure deployment is demanding but definitely doable and will be more of a challenge in countries with higher penetration rates. Still, Norway has already shown how to accommodate a more than 60% BEV share in new car registrations and is well on track to go fully electric by 2025.

Overall, setting a phasing out date for ICE cars may not only be beneficial for the climate and an important milestone in decarbonisation but open up new avenues to experiment with new forms of mobility. Improved public transport, a shift towards different modes of mobility (e.g. (e)bikes) and fully autonomous taxis would reduce the reliance on cars as well as decrease the necessity to own a car. The rapid growth of electric cars registrations is one of the few recent European success stories in this domain and demonstrates that rapid change is possible. This might encourage bolder interventions in other policy areas which are urgently needed. Europe should set a binding target to phase out fossil cars by 2030 simply because it is feasible and the right decision.